A the time of writing this post, Broccoli has an open pitch call for the second volume of Catnip, our delightfully feline print magazine. Hundreds of writers are sending in thousands of ideas, hoping for a commission. As I read through the pitches in Broccoli editors’ inbox, visions of writers dance through my head. Who are these people? Why do they want to write for us? Patterns emerge.

Some pitches are straight-up AI-generated word slop.

Hard pass.

Some enterprising souls have scanned our pitch call, quickly searched its themes, and banged out something on the first topic/keyword that came up. These are usually fairly generic; they often feature bullet points and bold type, as well as over-confident declamatory copy explaining why their pitch meets the brief. Sometimes, they read like rehashed Wikipedia entries.

Hard pass.

Some pitches are clearly repackaged; evidence of a writer with an idea shopping it around. (Now and then they are addressed to another editor or publication, which is extra funny.) These only tangentially touch on what we are asking for, and while I appreciate the hustle, they aren’t going to work.

Hard pass.

Some pitches are less studied; they meander. The writer is sweet and hopeful; they aren’t quite sure what they want to say, but they are reaching for something. But they may be reaching too far—these are the folks who would benefit from taking a little time before sending pitches out in the world. They need to discover who they are on the page first.

These, too, are a pass, albeit a gentler one.

And then there are the pitches whose writers have clearly invested some time and thought. They have read the pitch call; they have done a little research. They probably have a few bylines. They believe they have come up with an angle that works.

But they do not see what I see: Dozens and dozens of pitches that are basically the same as theirs—writers citing the exact same ideas and reference points.

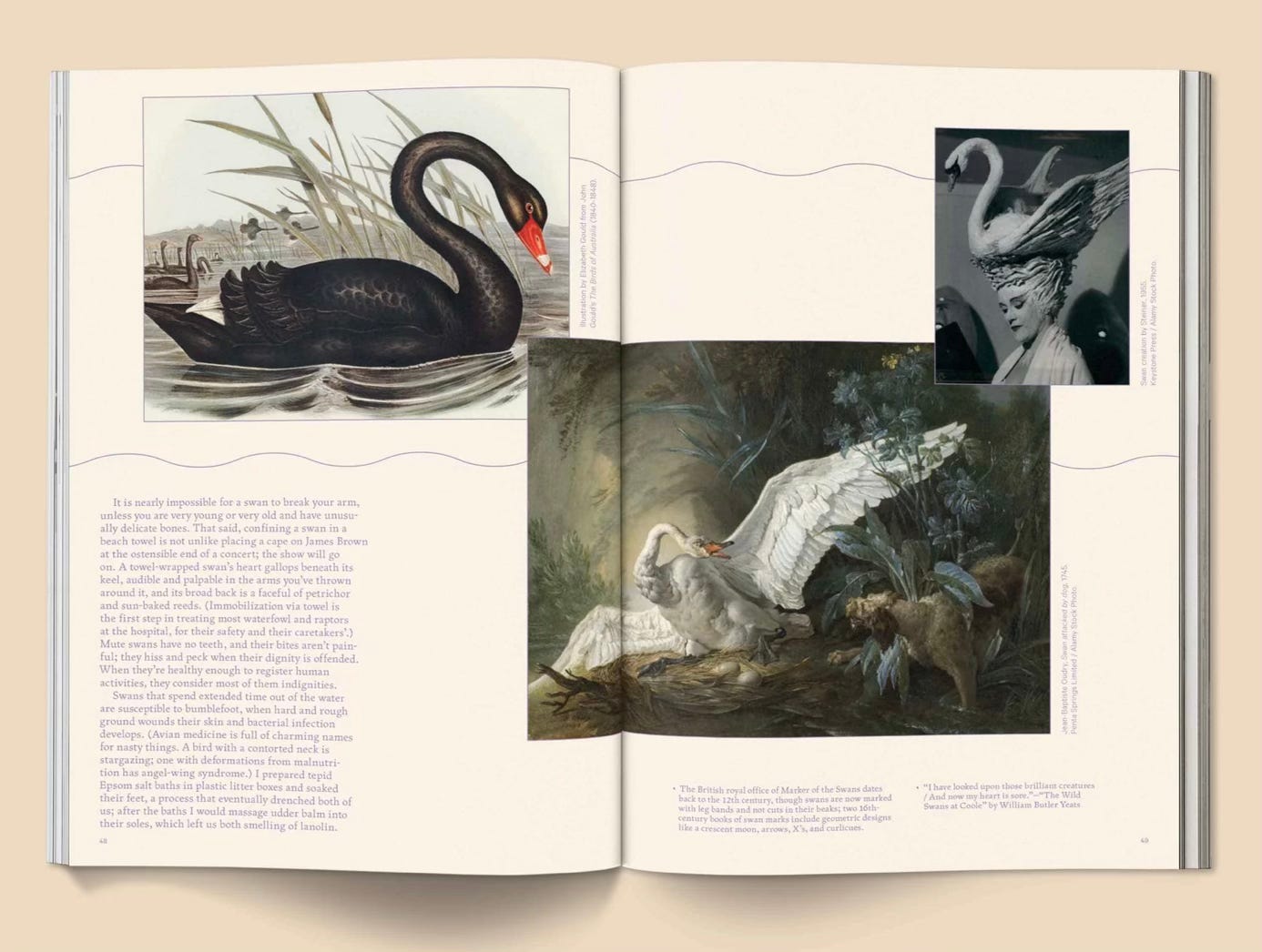

This happens all the time. We often throw out themes in our pitch calls and ask writers to pitch around these ideas. Right now, the Broccoli editors’ inbox is awash with oodles of pitches on cats in Ancient Egypt, witches’ cats, and cat cafés. In Broccoli Issue 20, we wanted a story on swans, so we included that in the pitch call. As a result, we were inundated with pitches on the ballet, Swan Lake, and swan fairy tales. Most hit on the same themes: beauty, death, love, yadda yadda yadda. Some were very well-written. We rejected them all. Two, though, stood out—one, from Lauren Oster, took us into her experiences working with swans in a wild bird rescue facility. The other, from Jami Nakamura Lin, was about her childhood fixation on a 1990s-era cartoon movie about a swan princess. Though we had originally planned to commission one piece, we were so enamored by these pitches that we had to have them both.

They each embodied something I’ve found to be true: The very best pitches are concise and compelling and immediately make us want to read more. They vary in tone, style, and approach, but the one thing that shines through is an element of singularity—the feeling of a specific mind and voice meeting a specific subject in a way that makes something magical happen.

Only Lauren had her experience of holding a wild swan. Only Jami had her memories of watching “The Swan Princess” over and over. Crucially, both are extraordinary writers and thinkers; their pieces took wing and flew in surprising directions. They each offered something wholly unique.

So what is a writer to do?

Push yourself.

There are no shortcuts in writing because there are no shortcuts in thinking. Be a little suspicious of your first idea—what floats to the top is often generic, too influenced by the zeitgeisty swirl. Take time. Give your thoughts a prod and a poke. Is there anything actually there under the surface? What do you really want to say? Go deeper. Get offline. Find inspiration that is not accessible by an easy Google search. Look for the throughline that is specific to you and you alone—the place only you can take a story. And while both pieces I mentioned were personal essays, here’s a reminder that all writing is always personal—everything you write comes from your mind and sensibility. So, no matter what you pitch, whether it is a reported feature, a Q&A, or, yes, a personal essay, it should bear the stamp of your particular mind, skill, and voice. And—this is key—only pitch stories you really want to write. Anything else is filler, and we don’t need that.

Many writers think pitches about their feelings and experiences are their best bet for getting noticed, but this is not true. After reading thousands of pitches, I can say that just about everything has happened to just about everyone. Everyone feels all the feelings. If you want to write about it for us, you need to bring something more to the table.

I know that most writing opportunities are about the churn—keywords, quick turnarounds, trends, surface. But Broccoli works in print for a reason. We hold a different place for writers—a freer, weirder, richer place. Don’t be afraid to stand out.

Stephanie Madewell,

Broccoli editor

Absolutely loved how you articulated what makes a strong pith. Thank you for this!

Thanks for helping to uplift (and fund) stories like the ones you’re calling for here… in a world of magazines obsessed with deadlines, timeliness, and attention-swallowing “content,” we really need more outlets that uplift this kind of heart and meaning-driven work. I just wish there were more spaces that would publish this type of writing and pay well for it — but I do sense that in our world of AI and ad-driven slop (great word choice) people will be craving this kind of writing more and more.